By Malik Bilal

In Pakistan’s evolving agricultural landscape, smallholder farmers face mounting challenges: pest outbreaks, climate variability, resource constraints and limited access to knowledge and modern practices. Over the past two decades, Farmer Field Schools (FFS) have emerged as a transformative approach to equip farmers with the skills, knowledge and decision-making capacity to address these challenges effectively.

Originating in Indonesia in 1989 under the Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) Integrated Pest Management (IPM) program, FFS was designed to shift the paradigm from top-down instruction to experiential, participatory learning. As International FFS expert Jam Muhammad Khalid emphasizes, “The Farmer Field School approach is about educating farmers in ecosystem literacy. It aims at making farmers expert, building local capacities in understanding food production ecosystems enabling resilient agriculture, bringing leveraging in market ultimately achieving FAO’s 4 betters: better food, nutrition, environment and life.” Farmers, guided by trained facilitators, observe, experiment and analyze conditions directly in their fields, making informed decisions based on ecological understanding rather than reliance on pesticides or standard prescriptions. This approach not only improves crop management but fosters a deeper understanding of the complex interactions between crops, pests, soil and climate.

Pakistan introduced FFS in the late 1990s, initially targeting cotton growers to mitigate pest-related losses. Over time, the program expanded to cover a wide range of crops, including maize, vegetables, citrus orchards and tobacco, across provinces such as Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. According to Khalid, this approach moves beyond singular issues: “The farmer field school approach has a potential to make farmers expert on landscape ecosystem as well, in comparison to working on minor production issues of a specific crop or crops. It has successfully demonstrated across the globe in empowering farmers, strengthening local extension services and job creation at local level.”

Studies consistently show that farmers participating in FFS achieve higher knowledge levels, adopt sustainable practices such as integrated pest management and improved irrigation and often experience increased yields and better economic returns compared to non-participants. In citrus orchards, for example, FFS participants have adopted drip irrigation, improved soil management and pest control measures that significantly enhance both yield and fruit quality. Similarly, maize farmers in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa report improved crop management, optimized seed rates and spacing and higher productivity following FFS interventions.

Beyond technical gains, FFS strengthens social capital and collective decision-making. Participating farmers engage in weekly sessions, reflect on observations and share experiences, creating networks that facilitate knowledge transfer and peer-to-peer learning. This includes targeted efforts for inclusion, as Khalid notes: “Different derivative models, as per the socio-cultural norms, are introduced for gender inclusiveness and mainstreaming in the agriculture food systems.” Initiatives such as “Women Open Schools” and climate-focused FFS variants underscore efforts to make these programs inclusive and adaptive to emerging challenges, including climate change and market access constraints.

Despite their proven benefits, FFS face limitations in Pakistan. Coverage remains limited, with many districts, marginalized communities and crops still under-served. Sustainability and long-term adoption of improved practices depend on ongoing support, access to inputs and institutional backing. Additionally, gender and inclusion challenges persist, as participation often skews toward male farmers with better resources or education. Scaling up these programs effectively requires trained facilitators, careful monitoring and integration with government extension services, markets and financial services.

Nevertheless, the evidence is clear: Farmer Field Schools represent a critical tool for building resilient, sustainable agriculture in Pakistan. For their full potential to be realized, systemic change is essential. The approach needs to be programmed and institutionalized within both public and private sector agriculture extension services across the country. FFS not only provide farmers with technical knowledge but also build the capacity to adapt to environmental and economic pressures, ultimately improving livelihoods and contributing to national food security.

As Pakistan faces increasingly complex agricultural challenges, expanding and strengthening FFS programs offers a pathway to empower smallholders and secure the future of the nation’s farms.

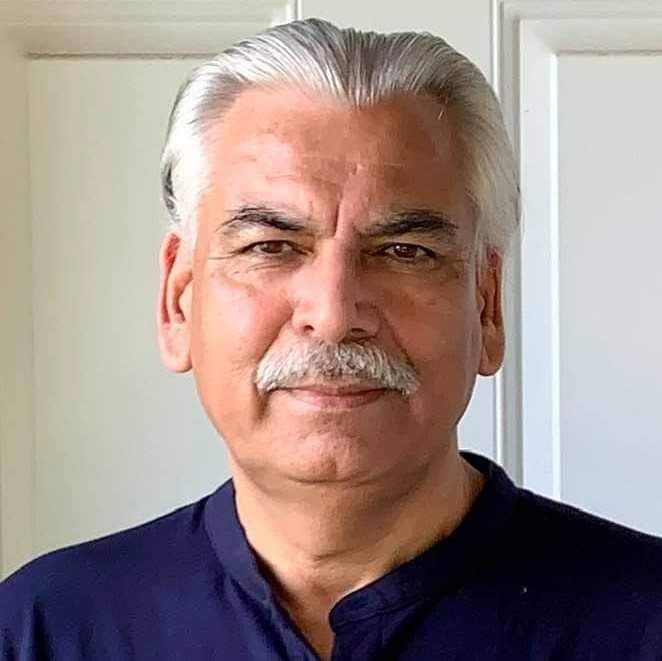

About the Author: Malik Bilal is a development and humanitarian professional with over 16 years of experience in emergency response, resilience building, climate governance and sustainable development across Pakistan. He specializes in programme management, field implementation and community-based livelihoods and can be reached at malikbilal1983@gmail.com

“Farmer Field Schools Empowering Pakistan’s Smallholders for Sustainable Agriculture”

Leave a Reply