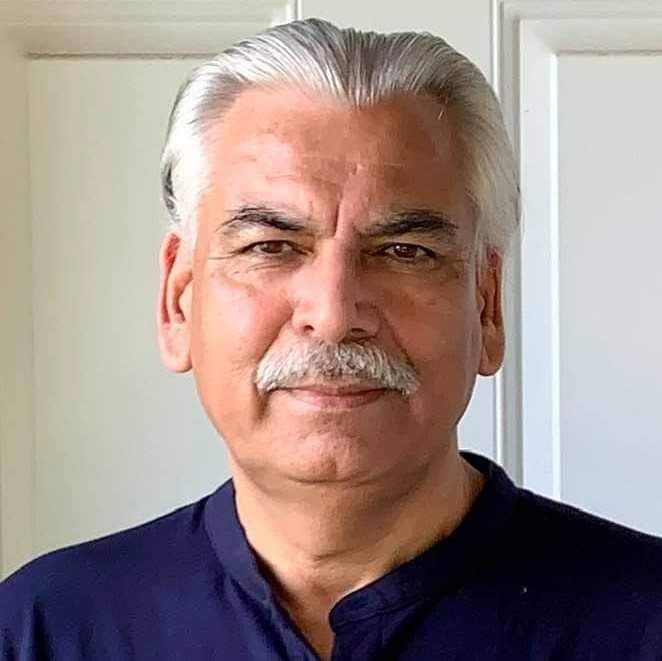

Barrister Usman Ali, Ph.D.

A reflection on selective principles, recurring power struggles, and why constitutional rhetoric fails to translate into democratic reform.

One of the most enduring and uncomfortable truths of Pakistani politics is that democracy is repeatedly invoked, but rarely internalized. Political speeches routinely begin with phrases like “my people” and “my fellow Pakistanis.” Voters are courted, crowds are mobilized, and citizens are placed at the front of rallies, marches, and protests. Yet when it comes to acquiring and sustaining power, faith is placed not in the public mandate but in the backing of powerful generals. And the moment that backing is withdrawn, the same “people” are suddenly rediscovered.

This contradiction was once again on display recently in Islamabad, where a two-day national conference was held at the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa House under the banner of the Movement for the Protection of the Constitution of Pakistan. Leaders from various political parties, lawyers, journalists, and civil society representatives participated. At its conclusion, a unanimous declaration reaffirmed commitments to constitutional supremacy, judicial independence, transparent elections, human rights, and democratic values. The conference demanded investigations into alleged rigging in the February 2024 elections, announced February 8, 2026 as an internationally observed “Black Day,” called for a nationwide wheel-jam and shutter-down strike, and echoed a call attributed to PTI founder Imran Khan to prepare for a street movement.

On the surface, the rhetoric was difficult to contest. The language was forceful, the demands broadly acceptable. But Pakistan’s political problem has rarely been about stated demands; it has been about intent, continuity, and credibility. The constitution, justice, and civil liberties are often remembered only after power slips away. While in office, these ideals are buried under the excuse of “political necessity.” Once in opposition, a sudden moral awakening follows. What was dismissed as falsehood in government is repackaged as absolute truth outside it.

This is why the conference struck many observers less as a moment of constitutional renewal and more as political repetition. Some faces had changed, but the claims were familiar, the anger unchanged, only the target had shifted.

Among the participants were PTI-affiliated leaders, lawyers, and politically aligned commentators who, during PTI’s time in power, justified false cases, convictions, media trials, and a range of unconstitutional measures against the opposition. These actions were then presented as strengthening democracy, safeguarding judicial independence, and protecting constitutional order. Today, the same vocabulary is being deployed against the current government.

If “judicial independence” once meant verdicts against political rivals, why do rulings against one’s own side now constitute “judicial subservience”? If the 2018 elections were celebrated as transparent because they produced victory, how did elections conducted in a similar manner in 2024 suddenly become illegitimate? Principles, if they are genuine, cannot change with position. Otherwise, the uncomfortable truth remains that in Pakistan the constitution is too often treated as a tool of convenience rather than a shared destination.

This cyclical behavior has consistently weakened the political system. Laws fail to gain authority, justice loses credibility, and democracy remains stagnant.

The conference also drew applause for its fiery calls for “resistance” and “taking to the streets.” But this raises a fundamental question: who will resist, and who will bear the cost? In Pakistan, revolutionary rhetoric is often delivered by those whose political journeys have followed relatively secure paths, while the burden is shouldered by those already struggling with inflation, unemployment, and state pressure.

As has frequently happened, several speeches explicitly urged Pashtuns to once again occupy the front lines of protest. Those making such appeals typically record messages from the comfort of their vehicles, upload them to social media, and disappear. Pashtuns, meanwhile, are mobilized in the name of bravery and loyalty, turning them into expendable participants. Even today, Pashtuns imprisoned after previous protests remain largely forgotten, without sustained advocacy.

This is the point where constitutional struggle must move beyond the poetry of rally stages and evolve into a serious national strategy. If the Movement for the Protection of the Constitution genuinely seeks constitutional supremacy, it must abandon selective principles. What is unacceptable when imposed on one’s allies must remain unacceptable when imposed on opponents. Restrictions condemned as oppression in opposition cannot become governance tools in power. Otherwise, the public will continue to view such movements as little more than power struggles.

If today’s opposition truly seeks reform and the rule of law, it should demand impartial investigations into both the 2018 and 2024 elections. It should also call for non-partisan accountability of all generals, judges, journalists, and politicians who, particularly over the past fifteen years, have played a role in distorting Pakistan’s political and social order.

Another question must be confronted honestly: is resistance the only path? History suggests that when resistance lacks a clear, peaceful, and constitutional roadmap, one of two outcomes follows. Either the state escalates repression, or the movement fractures internally. In both cases, ordinary citizens pay the price. Many of those delivering the loudest revolutionary speeches lack both the credibility and capacity to mobilize sustained public action, and are unlikely to appear on the streets themselves.

Even if one assumes that large numbers of citizens do mobilize, Pakistan’s history offers a sobering reminder. The political upheaval of 1977 demonstrated how movements without institutional grounding can end with everything lost, leaders, structures, and democratic space alike.

If constitutional awareness is truly the objective, several difficult but essential steps are unavoidable: internal accountability, clear and actionable demands, an unambiguous commitment to non-violence, and genuinely inclusive participation across regions and communities. Defending the constitution is not merely about challenging those in power; it also requires acknowledging one’s own failures and holding even favored leaders within the bounds of law.

The central question, ultimately, is simple: do we want a constitution that belongs to all citizens, or one that serves shifting political interests?

If politicians on both sides, government and opposition, have truly recognized that the current path leads nowhere, then the moment has arrived to replace emotion, hatred, and revenge with dialogue, reconciliation, and reason.

Enough has been thought through for personal advantage. It is time to think for the public.

Otherwise, conferences will continue, declarations will be issued, and the people, as always, will keep paying the price. Perhaps it is also time for the public itself to reflect on its role in this recurring political spectacle, and to decide consciously what comes next.

Leave a Reply